Panic attacks are real. They hit unexpectedly, the intensity of the fear is extreme, and the urgency is immediate and all consuming. They may last only a few minutes or hours. They begin with intense apprehension, a fear that something is about to go dreadfully wrong, even fear that one is about to die. The body is reacting and showing all the signs of the growing crisis: shortness of breath, rapid heart rate, dizziness, sweating, upset stomach, and more.

Panic attack, a recognized disorder

A panic attack is a recognized disorder. The World Health Organization describes the disorder as, “an episode of intense fear accompanied by symptoms such as heart palpitations, sweating and chills or hot flushes, a sensation of dyspnea (difficulty breathing), chest pain, abdominal distress, depersonalization, fear of going crazy, and fear of dying.” (Definition from the International Classification of Disease, ICD-10)

People who suffer from this disorder may initially not realize what is going on. They experience the physical symptoms and look for physical explanations, like heart disease, thyroid problems or other illnesses. They may end up making many trips to their physician or the emergency room, convinced that something very serious is wrong with them without ever receiving a satisfactory diagnosis.

At some point in this process, people may withdraw and stop looking for explanations as they feel that people around them are starting to question their sanity. They may even start believing it themselves, that maybe they are hypochondriacs and should just ‘get over it’.

The good news is that this condition is a very treatable disorder. People who suffer from panic attacks can get help. With the right approach from skilled clinicians, they can indeed get over it.

Understanding panic attacks

Panic disorder is not that rare. Over 20% of the adult population experiencing one or more panic attacks during their lifetime. (Kessler, 2006)

A panic attack is the response of the body to a threat that does not exist. The body enters a so-called ‘fight-or-flight’ mode (Graeff, 2008), but there is no actual danger present.

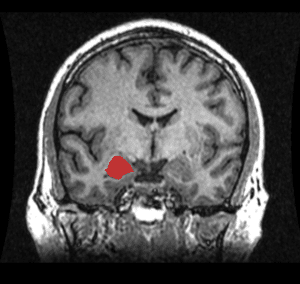

MRI showing the location of the amygdala

It is not clear what the exact pathophysiological mechanism is that causes panic attacks. Researchers point to various factors as possible culprits, from genetic causes to chemical triggers or heightened sensitivity to internal autonomic cues (e.g., increased heart rate). The amygdala is thought to play a pivotal role in the development of panic disorder. (Shekhar, 2003) The amygdala is a cluster of cells deep in the brain. The structure is closely involved in the experience of emotions, especially fear. Researchers believe that sufferers from panic disorder have developed abnormal processing in this part of the brain, leading them to enter the fight or flight response without a threatening trigger in their environment. (Kim, 2012)

The sympathetic nervous system

The part of the nervous system that plays a key role in preparing the body for fight or flight is the sympathetic nervous system. The sympathetic nervous system is part of the autonomic nervous system, the system over which we have no volitional control.

The Sympathetic Nervous System

When the sympathetic nervous system is activated, the priorities of the body are totally focused on action – muscles tense up, blood supply is diverted away from the digestive system towards the large muscle groups, heart rate and blood pressure rise, and sensitivity to light, sound and touch all increase. In this state the body is hyper alert, toned up and ready to act at peak performance (fight or run).

This response is very functional and appropriate when one is in a dangerous situation where action is essential to avoid personal harm. However, the response is dysfunctional when there is no actual danger and can even lead to persistent physical symptoms if it happens repeatedly. This can be better understood by examining how the sympathetic nervous system works and what influence it has on the musculoskeletal system.

The sympathetic nervous system has influence on organs like the heart and the lungs as mentioned above. The influence of the sympathetic nervous system on the musculoskeletal system is very specific:

- Muscle tone increases

- Muscles, skin and tendons become more sensitive

- Circulation in the fine capillary network decreases

All is well if this occurs just temporarily, when reacting to some emergency. But if this happens repeatedly and for longer periods of time, the tissues eventually get damaged. They receive too little oxygen because the blood supply is reduced; the muscles and tendons become painful because of the ongoing tension; the skin may become painful to touch. Once a person has reached this state, the symptoms of the sympathetic nervous system hyperactivity become a source of irritation and the situation is becoming a chronic state of physical and emotional dis-ease.

Dealing with panic disorder

The information discussed above paints a picture of a vicious cycle:

- The brain triggers a fear response for some unknown reason;

- This leads to an over-activation of the sympathetic nervous system;

- In turn this may cause chronic physical symptoms of pain and discomfort;

- Eventually these symptoms exacerbate the fear response (“Am I having a heart attack?”; “What is wrong with me?” “I think I’m dying.”)

People trapped in this cycle need help. The good news is that the condition is very treatable. Studies suggest that the prognosis of patients suffering from panic disorder is very good with over 80% of patients who receive some combination of medication and psychotherapy achieve remission within 6 months.

The key to dealing with panic disorder is to get help from a knowledgeable and skilled clinician. The approach should involve interventions that tackle the problem from various angles:

- A physician may prescribe medication.

- A psychotherapist will use techniques like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy to teach the client to process thoughts and emotions to interrupt the attack when it happens. (Click here to read a blog post on CBT techniques.)

- A physical therapist may help deal with the physical symptoms that have developed over time, like chronic pain points and trigger points.

Not everyone will need to receive care from all 3 disciplines but some combination of interventions from the various fields will produce the best results.

The best advice for sufferers from panic attacks: get help! If you do, you are very likely to recover.

Click here to learn more about the process.

References

Graeff, Frederico G., and Cristina M. Del-Ben. “Neurobiology of panic disorder: from animal models to brain neuroimaging.” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 32.7 (2008): 1326-1335.

Kessler, Ronald C., et al. “The epidemiology of panic attacks, panic disorder, and agoraphobia in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication.” Archives of general psychiatry 63.4 (2006): 415-424.

Kim, Jieun E., Stephen R. Dager, and In Kyoon Lyoo. “The role of the amygdala in the pathophysiology of panic disorder: evidence from neuroimaging studies.” Biology of mood & anxiety disorders 2.1 (2012): 20.

Shekhar, Anantha, et al. “The amygdala, panic disorder, and cardiovascular responses.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 985.1 (2003): 308-325.